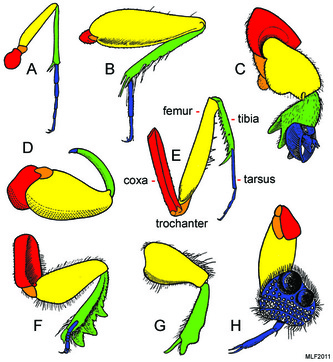

Insects have a total of six legs, including a pair of fore, mid and hind legs, which are found on the pro-, meso- and metathorax respectively (Cranston & Gullan, 2010). Each leg is divided into six segments, which, starting from the top of the leg are called the coxa, trochanter, femur, tibia, tarsus and post-tarsus (Chapman, 1998). The tarsus then has 5 'pseudo-segments', which are not true segments because they are all connected by the same muscles (Cranston & Gullan, 2010). Instead, these compartments are called 'tarsomeres'. The post-tarsus is usually equipped with pulvilli, which are smooth or hairy pads used in adhesion (Cranston & Gullan, 2010).

While the femur and tibia are usually the largest segments of the leg, there is a great deal of modification depending the insect's lifestyle. For example, walking or running insects, such as the cockroach or stick insect, have well developed femur and tibia on all legs, while jumping insects like the grasshopper have disproportionately sized hind femur and tibia, giving them the strength to jump great distances (Cranston & Gullan, 2010). Swimming insects usually have tarsi and tibia bearing long fringes of hair used to propel them through the water, and digging insects have largely modified fore tibia to enable them to dig efficiently (figure 1) (Chapman, 1998).

While the femur and tibia are usually the largest segments of the leg, there is a great deal of modification depending the insect's lifestyle. For example, walking or running insects, such as the cockroach or stick insect, have well developed femur and tibia on all legs, while jumping insects like the grasshopper have disproportionately sized hind femur and tibia, giving them the strength to jump great distances (Cranston & Gullan, 2010). Swimming insects usually have tarsi and tibia bearing long fringes of hair used to propel them through the water, and digging insects have largely modified fore tibia to enable them to dig efficiently (figure 1) (Chapman, 1998).

It is very important that the insect is able to get a strong grip on the substrate, in order to get the leverage needed to propel the body forward (Cranston & Gullan, 2010). This anchorage can be achieved by claws on the insect's feet that can attach to even the slightest roughness on the substrate (Cranston & Gullan, 2010). On completely smooth surfaces, pads covered in fine hairs are lubricated, and the close-range molecular forces between the hair and the surface act to anchor the insect (Chapman, 1998).

Although there are large variations among insect leg anatomy, roboticists are most interested in the legs of insects such as cockroaches (Order Blattodea) and stick insects (Order Phasmatodea), as these insects are 'walking' insects (Karalarli, 2003). The walking mechanisms of these orders have been studied and mimicked for hexapod robot use.

Although there are large variations among insect leg anatomy, roboticists are most interested in the legs of insects such as cockroaches (Order Blattodea) and stick insects (Order Phasmatodea), as these insects are 'walking' insects (Karalarli, 2003). The walking mechanisms of these orders have been studied and mimicked for hexapod robot use.